ONE YEAR LATER, SURVIVORS OF THE CHARLESTON SHOOTINGS AGREED TO THIS SERIES OF FOLLOW-UP PORTRAITS BY PHOTOGRAPHER JONATHAN HANSON.

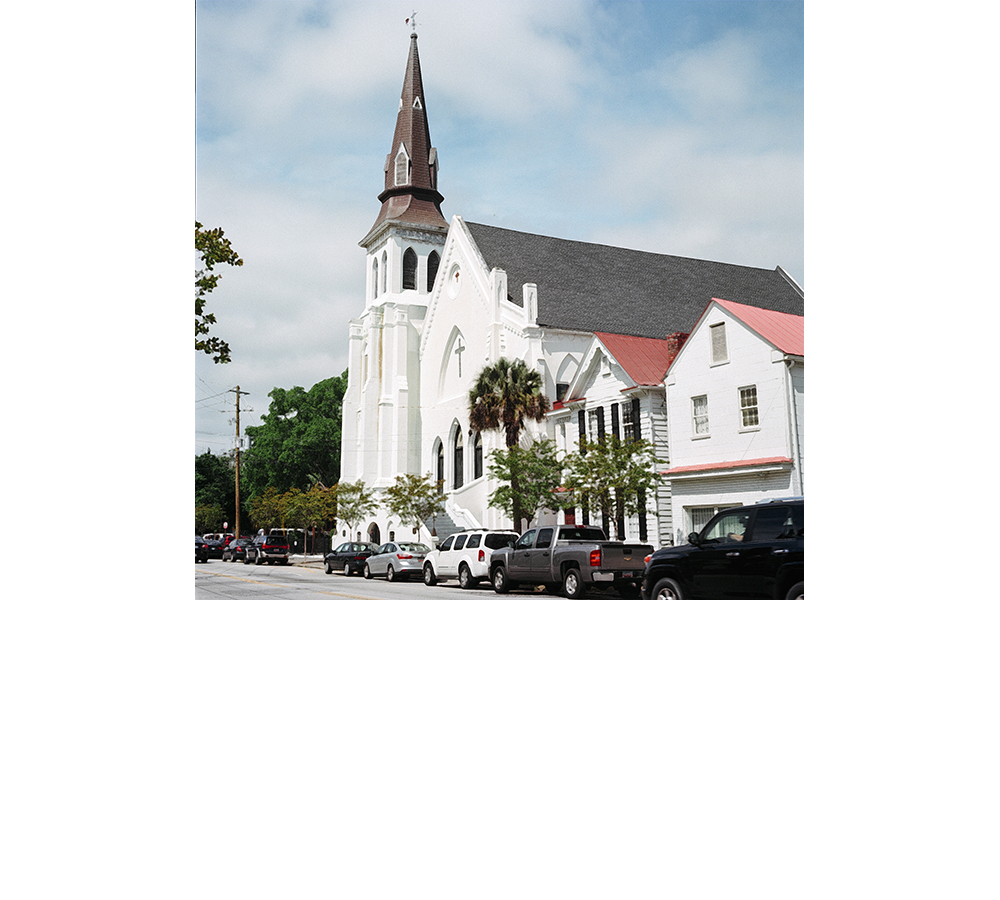

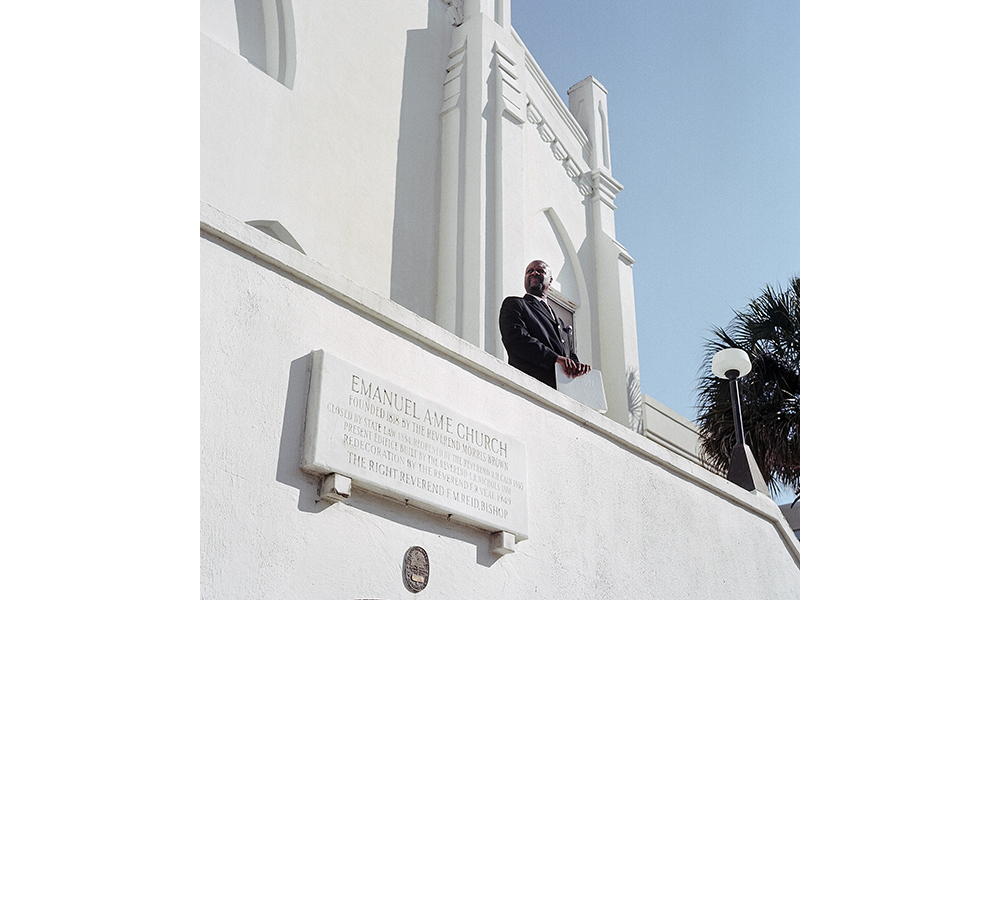

On June 17th, 2015, one hour into a Wednesday night bible study, nine people were shot dead by a gunman at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Two days later, family members of the victims spoke to the killer during his bond hearing, and spoke words of forgiveness. Victims included: DePayne Middleton Doctor, Cynthia Hurd, Susie Jackson, Ethel Lance, Clementa Pinckney, Tywanza Sanders, Daniel Simmons, Sharonda Singleton and Myra Thompson. A year later, as family members and a congregation try to cope with what happened, the trauma from the shooting adds to the 300-year-history of racial violence and bigotry in this country. The church itself is 197-years-old. It was burned to the ground once, and its co-founder, Denmark Vesey, was murdered for planning a slave revolt in 1822; resilience is in it’s blood.

A member and volunteer at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, checks for straggling church members just before Sunday service begins. Three people survived the shooting last June: Felecia Sanders, Sanders’ granddaughter Camia Terry, and Polly Sheppard. Sanders and her eleven-year-old granddaughter pretended to be dead while laying under a table. When the shooting was over, Polly Sheppard, who had also been hiding under a table, looked Dylan Roof in the eye. "He said, ‘Shut up. Did I shoot you yet?' I said, 'No.' And he said, 'I'm not going to. I'm going to leave you here to tell the story.”

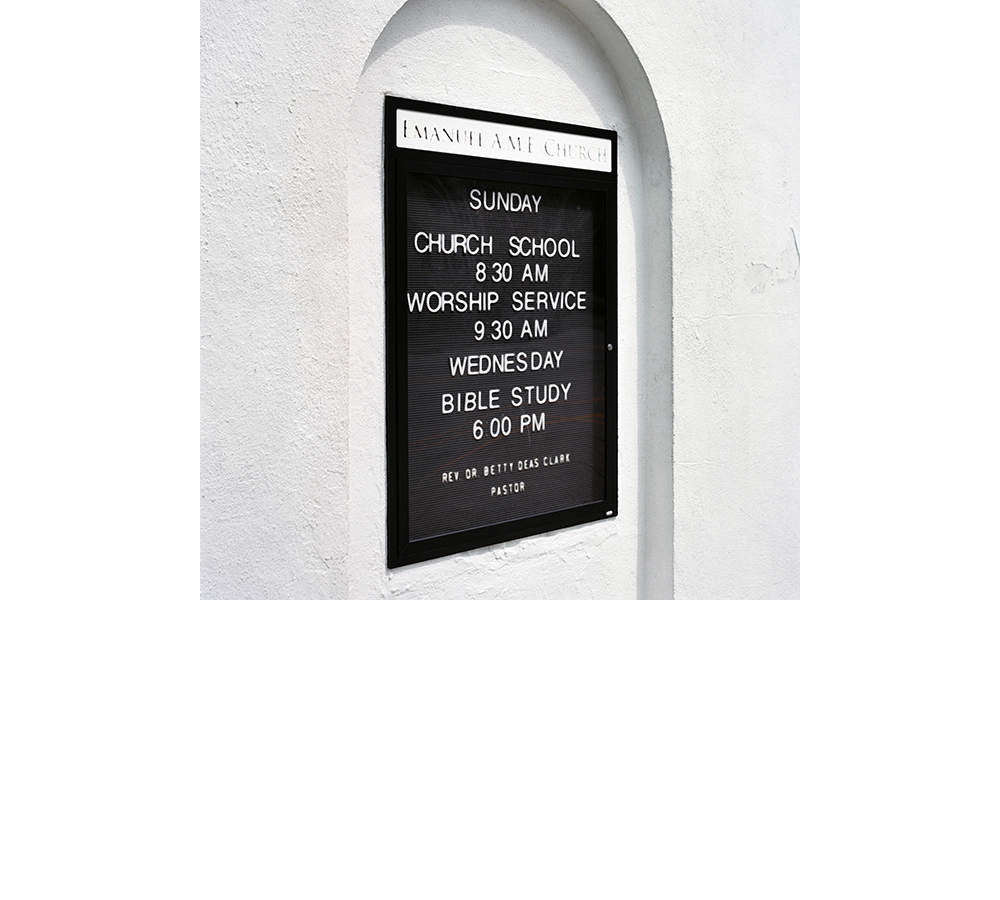

The bulletin board outside Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston posts the times for service and bible study. The church has a long history of faith that has seen them through hard times. "We didn't just arrive here," Reverend Clark said, as we talked in her office about the importance of their denominational identity. They know who they are, and where they come from. The suffering and endurance of their past has given them strength for the future. The forgiveness that family members shared with the killer is rooted in that identity. Wednesday night bible study continues at the same time, a year later. “It’s the middle of the week, it’s hard to get even regular members to come. So when you get someone new, you’re excited. You think, ‘Somehow this person found their way to us, and we are going to do our best to spread Christ’s love. This is our guest, and we’re going to love on them while they’re here.’ That’s the way it’s supposed to be.” Says Shirrene Goss, sister of Tywanza Sanders, one of the nine killed.

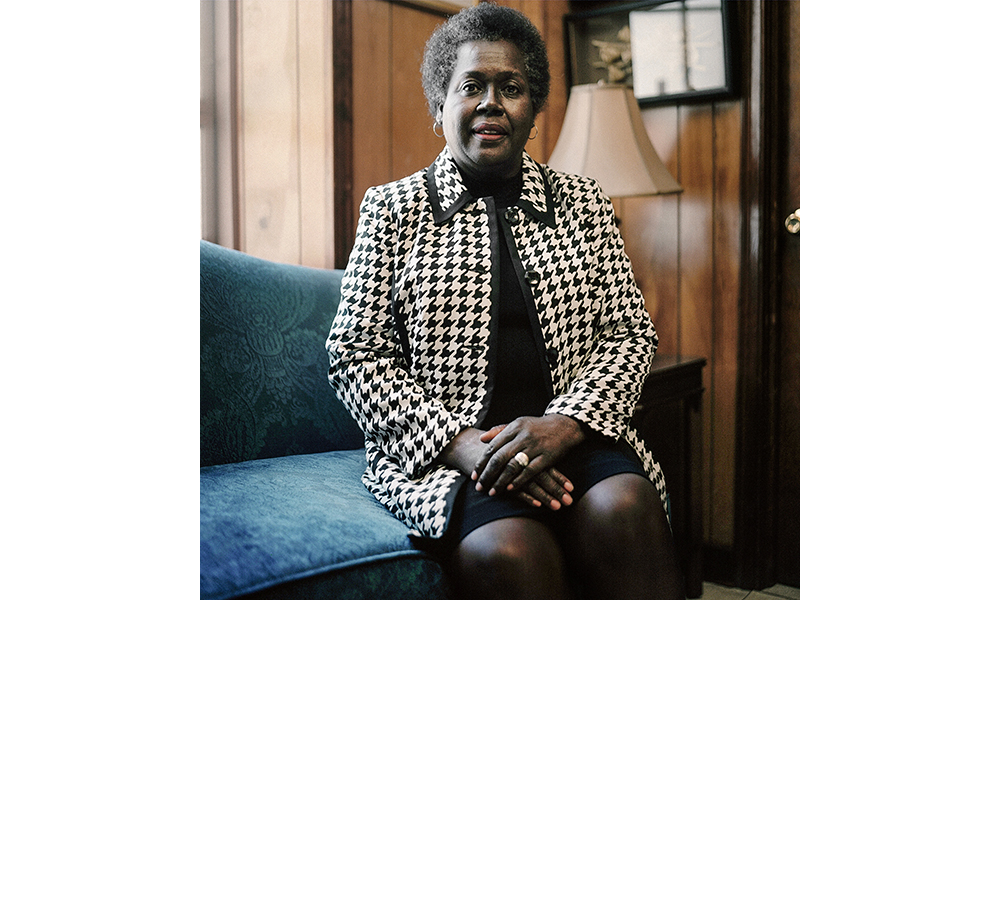

Pastor Betty Clark greets a visitor after Sunday service at Mother Emanuel AME Church. The killer, Dylan Roof, chose the church because of its historic significance, and thrust the aging church into the international spotlight. “We haven’t had a chance to grieve,” says Pastor Clark, as we talked about the constant stream of visitors who have made the church a pilgrimage site. An historically black church, Sunday service is now attended by whites as well, integrating the church almost overnight. Other members I spoke with felt their grief had been stolen from them, through other people talking about the massacre and what it means, holding events inspired by it, and feeling that those events and conversations did not include them.

Pastor Betty Clark sits for a portrait in the basement and community room at Mother Emanuel AME Church after a Sunday service. Clark took over pastoral care of the church in January of 2016, but was reassigned in June, to an AME church in Georgetown. Clark’s predecessor, interim-pastor Norvell Goff, took over after the shooting which left Clementa Pinckney, the pastor at the time, dead. Goff was praised for reopening the church the Sunday after the shooting, but some of the victims’ families felt abandoned; saying there were no calls, and no meals or pastoral visits in the days following the shooting. Pastor Clark is now tasked with mending the congregation’s wounds, and to help do that she is drawing on the church’s long history of adversity. It has survived a burning, an earthquake, and a ban against worship, as a black church in the time of slavery.

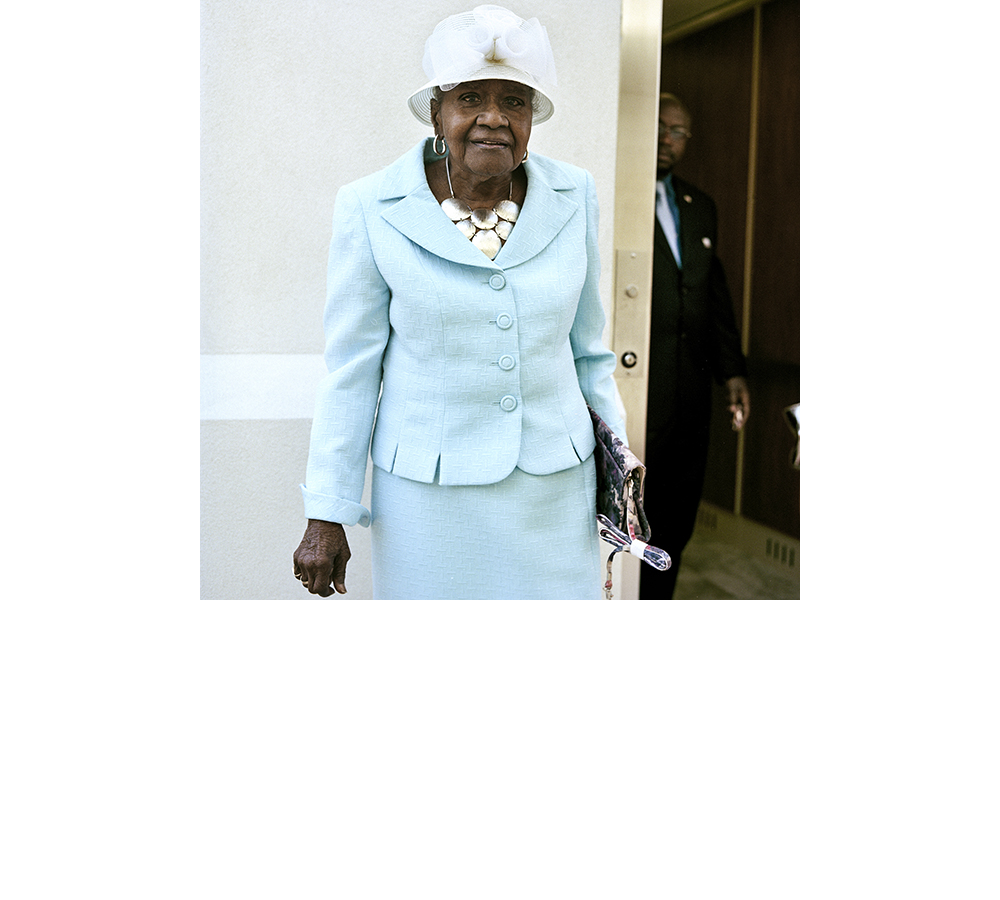

Mrs. Dixon, eighty-eight, has been attending Mother Emanuel AME Church for over eighty years, and says she’s a lifetime member. She is a retired school teacher and still attends Sunday service, despite the mass shooting that took place in the basement of the church during a bible study last year. The church’s congregation is aging with mostly lifetime members, but after the shooting it has seen a resurgence of interest from around the world. The church has become a pilgrimage site and a tourist destination, with people taking selfies in front, and lining the pews during Sunday service. Some feel they have not had the chance to grieve because of the spotlight. How do you live, how do you move forward, after suddenly becoming a symbol?

Avery Williams, fifteen, is an acolyte at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Pictured, he stands in front of the church before Sunday service. He is a young face in the aging church that is now in the spotlight after the mass shooting. Dylan Roof chose the church because of its historical significance, hoping to start a race war. Instead, Mother Emanuel and the Charleston community have come together to embrace racial differences. Days after the shooting, the family members of the victims spoke to Roof at his bond hearing, and offered up words of forgiveness. I spent time with the surviving family members and congregation, exploring their fragile forgiveness through an intimate portrait series.

Darius Coaxum (Left) and Bob Sanders (Right) have been attending Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston for around seventy-five years. They both attend Sunday service regularly, despite the mass shooting.

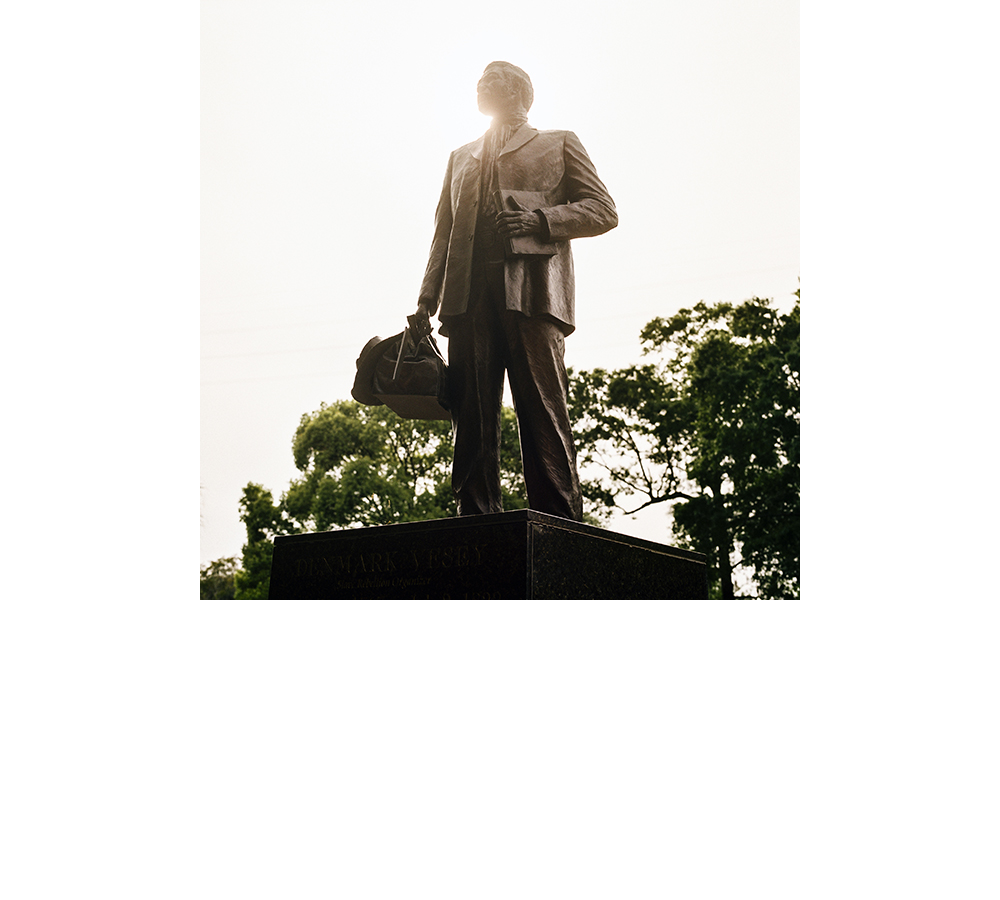

A statue of Denmark Vesey, co-founder of Mother Emanuel AME Church, stands in Hampton Park, in Charleston. Vesey was executed, and the original church was burned when he was charged with planning a slave revolt in 1822. That history was recognized in 2014, when the statue was erected. The revolt was to take place at midnight on June 16th, making the actual date for the revolt June 17th. Almost two-hundred years later, on June 17th, 2015, a gunman attended a bible study at the church, and opened fire, killing nine. Either Dylan Roof knew the importance of this date, or it was a coincidence. Days after the shooting, he said he had hoped to spark a race war through his actions.

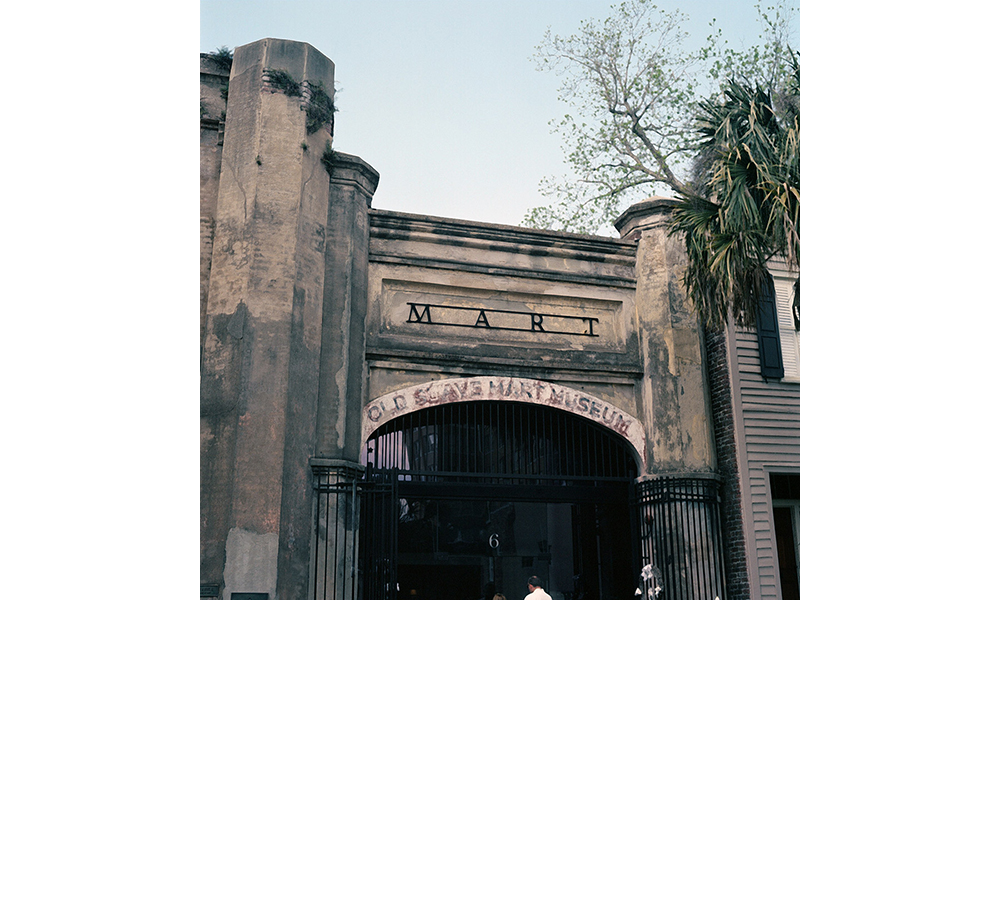

The Old Slave Mart is the last remaining building in Charleston to be used as a slave auction house. Now it stands as a museum, displaying Charleston’s history with slavery. In a city filled with reminders of the racists past, how does a community move forward after a racist gunman killed 9 at Mother Emanuel AME Church on June 17th, 2015.

Down the street from Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston stands a statue honoring John C. Calhoun, an historical proponent of slavery. His statue stands in front an armory in Marion Square, which was built to suppress slave rebellions after Denmark Vesey’s revolt was foiled, before it could happen. Marion Square would later become the Citadel. In 1837, Calhoun told the Senate, “[Slavery] cannot be subverted without drenching the country in blood, and extirpating one or the other of the races.’ He went on to say, “Nor should slavery ever be ended, because it is ‘a positive good.’” His idea rests solely on the racist notion that slavery is good for black people because they are, in his words, “low, degraded, and savage.” Further, he threatened the south’s secession and pushed for South Carolina to become a closed society, making abolitionist materials illegal, and stating that the constitution protected slavery. Knowing this long and complicated history, how do the family members of the victims forgive Dylan Roof who used hate to kill nine innocent people during a bible study? What are the next steps for Charleston, and the Mother Emanuel AME church as they try to mend these deep wounds?

Months after the mass shooting on June 17th, 2015 that killed nine at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, cadets from the Citadel painted “Charleston Strong” along a wall lining the academy’s old baseball stadium, on Rutledge Avenue. Residents were invited to stencil doves along the wall, symbolic of the nine doves shown on a flag that represented the nine victims.

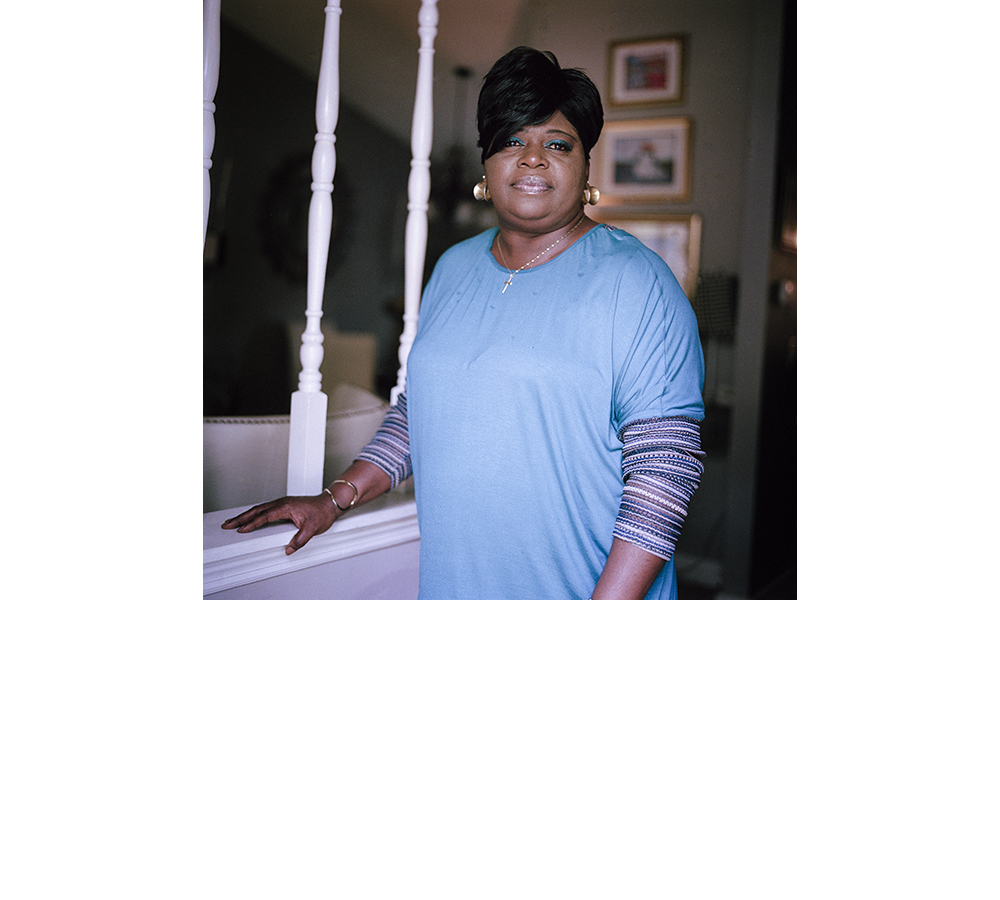

Nadine Collier’s mother, Ethel Lance, was murdered during that Wednesday night bible study at Mother Emanuel AME Church. During Roof’s bond hearing two days later, Collier was the first to speak to him, offering up forgiveness. She said, “I forgive you. You took something very precious away from me. I will never get to talk to her ever again—but I forgive you, and have mercy on your soul. . . . You hurt me. You hurt a lot of people. If God forgives you, I forgive you.” That’s what her mother Ethel would have wanted, she later told me. Nadine said, “Forgiveness is power. It means you can fight everything and anything head on.” Her mother was an usher at Mother Emanuel AME Church, which was a home for her family. Her grandmother was also a member of the church, and Nadine grew up there, and was often there as an adult. Since the shooting she has only returned once, on her mother’s birthday. “Lord knows, that damn near killed me,” she said. “When I got in there, I tell you I got so cold,” she said. “I cried the whole time I was there. It’s never going to be the same.”

Nadine Collier keeps a portrait of her mother Ethel on her living room table, along with some of the trinkets she used to buy her from thrift stores as gifts. The two talked every day, and Ethel would often stop in to visit, especially when Collier’s grandson, E.J., was around. He called them both “Granny.” “I could just be washing dishes, and I can feel my momma’s spirit come around me,” said Collier. “And she tells me, ‘It’s going to be okay.’” Since the shooting, Collier has had to grieve without the comfort of her church. She has decided to attend a different church because she can’t be in the same place her mother was murdered, and like other family members and survivors, Nadine felt abandoned in the aftermath of the shooting. No calls. No prayers from the new interim pastor. No spiritual care. “The people who were in higher places should have conducted things better,” she said. “I understand this is something new to them. It’s new to everybody. That was the time we needed them the most.”

Reverend Anthony Thompson sits in the living he once shared with his wife, Myra Thompson, who was killed in the June 17th shooting. Thompson, a retired probation officer and pastor at Holy Trinity Reformed Episcopal Church, helped Myra prepare the Bible study she taught that night. He spent hours at the dining room table with her, going over the text till she was satisfied. When he last saw her, Myra was finishing up some last minute notes, just before she left. She seemed to glow, he said, as if everything were right in the world. Then she walked out the door before he’d had the chance to say goodbye. Reverend Thompson had hoped to attend the Bible study that night, but Myra told him not to; his church was kicking off Vacation Bible School that night, and he was needed there. So after he finished up at his church, he stopped to pick up dinner for the two of them. As he sit waiting at home for Myra, with food on the table, he received a call that something terrible had happened at Mother Emanuel.

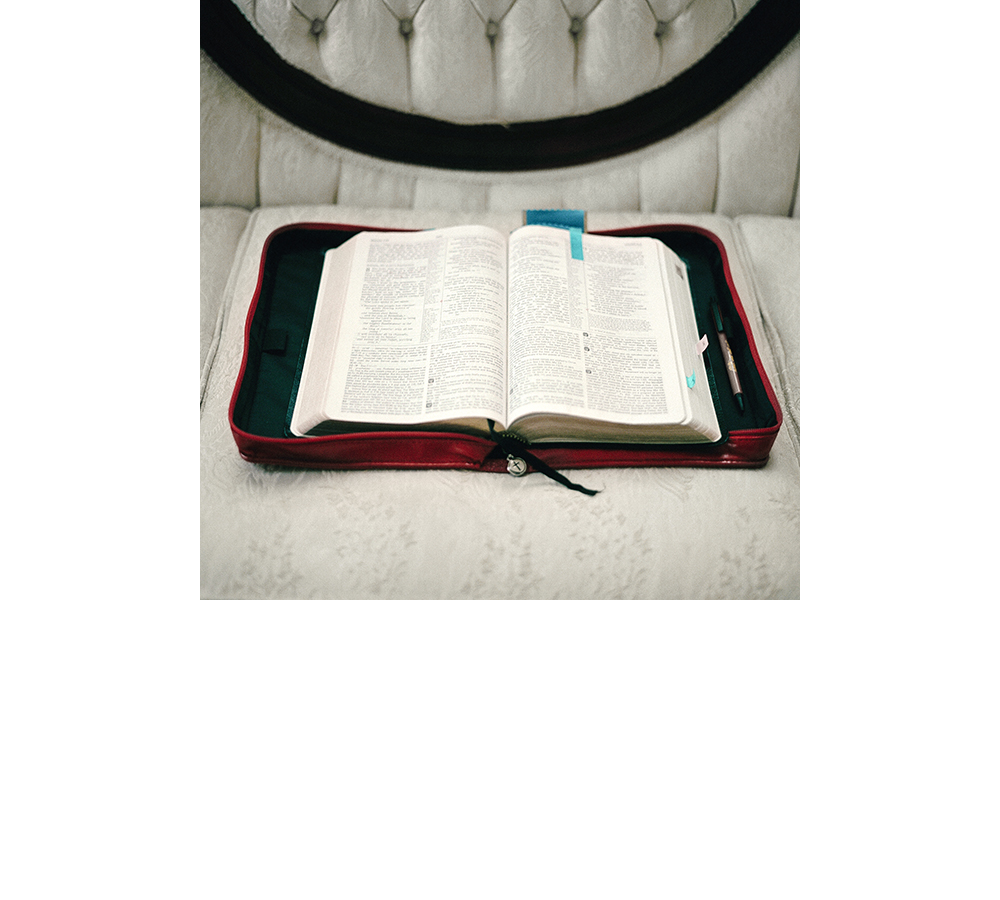

Myra Thompson’s bible, opened to the page she taught from the evening she was killed. After Myra’s murder, and Dylan Roof’s arrest, her husband Anthony spoke up at the bond hearing for Roof, and forgave him. And then he shared the gospel with his wife’s murderer. “We would like you to take this opportunity to repent,” the preacher told Roof. “Repent. Confess. Give your life to the one who matters most: Christ. So that he can change it.” During an interview in late April, Thompson said he hadn’t planned on attending that bond hearing, but something prompted him to go. In the courtroom, Thompson felt God speak to him, telling him to forgive Roof. “I wasn’t thinking about him,” he said. “I wasn’t planning on going. But God put it in my head. It was like He was speaking through me.” After the hearing, Thompson felt a sense of peace.

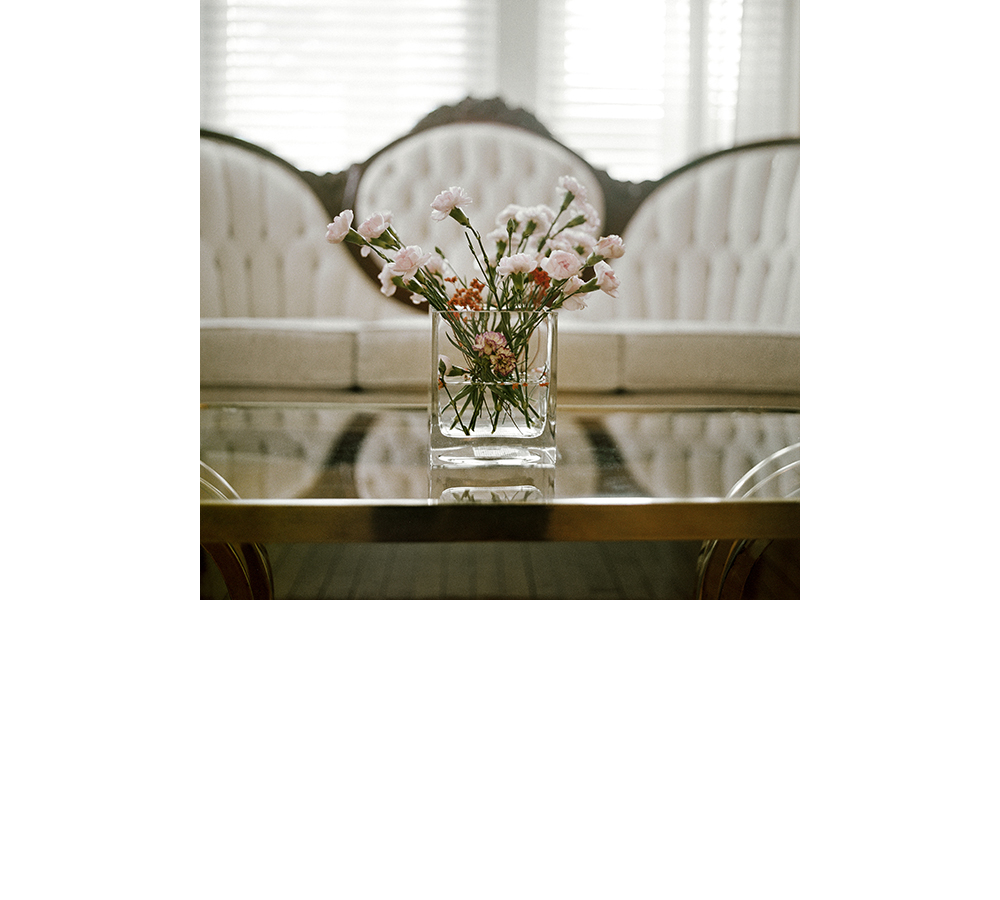

Myra Thompson was a victim of the deadly mass shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church. Her husband Anthony Thompson continues to keep flowers on the living room table, just as Myra did, refreshing them every week.

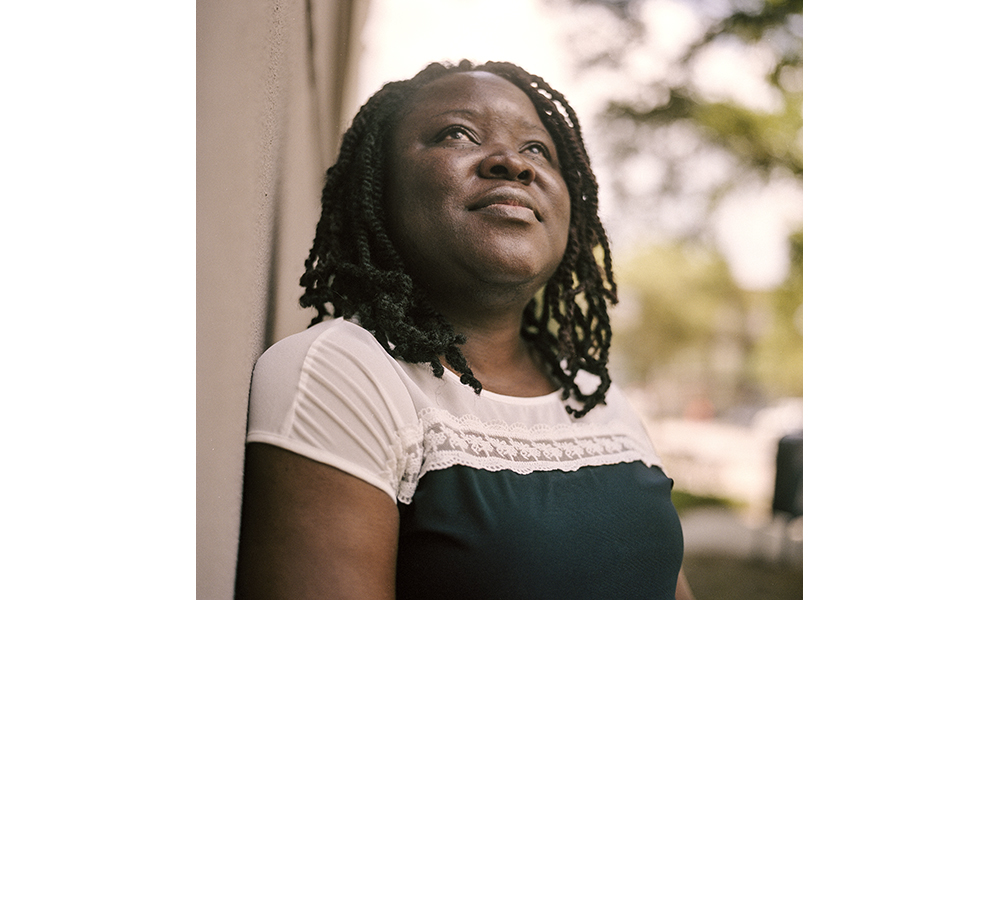

Shirrene Goss was hit hard by the mass shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church. She lost her brother, Tywanza Sanders, and her aunt, Susie Jackson. Her mother, Felicia Sanders, was also at the Bible study, but survived by diving to the ground with her granddaughter and playing dead. Shirrene attended Mother Emanuel growing up, and joined its Young People’s Department as a young adult. When asked about forgiveness, she says she has not grieved yet. “At this point, I can’t say I have forgiven. As a believer, I know that I have to.” she said. “When life has to go on—what can you do?” She stays busy raising her children, and helping her parents. She was not at the bond hearing for Roof, but plans to be in the courtroom at his trial, set for January 2017.

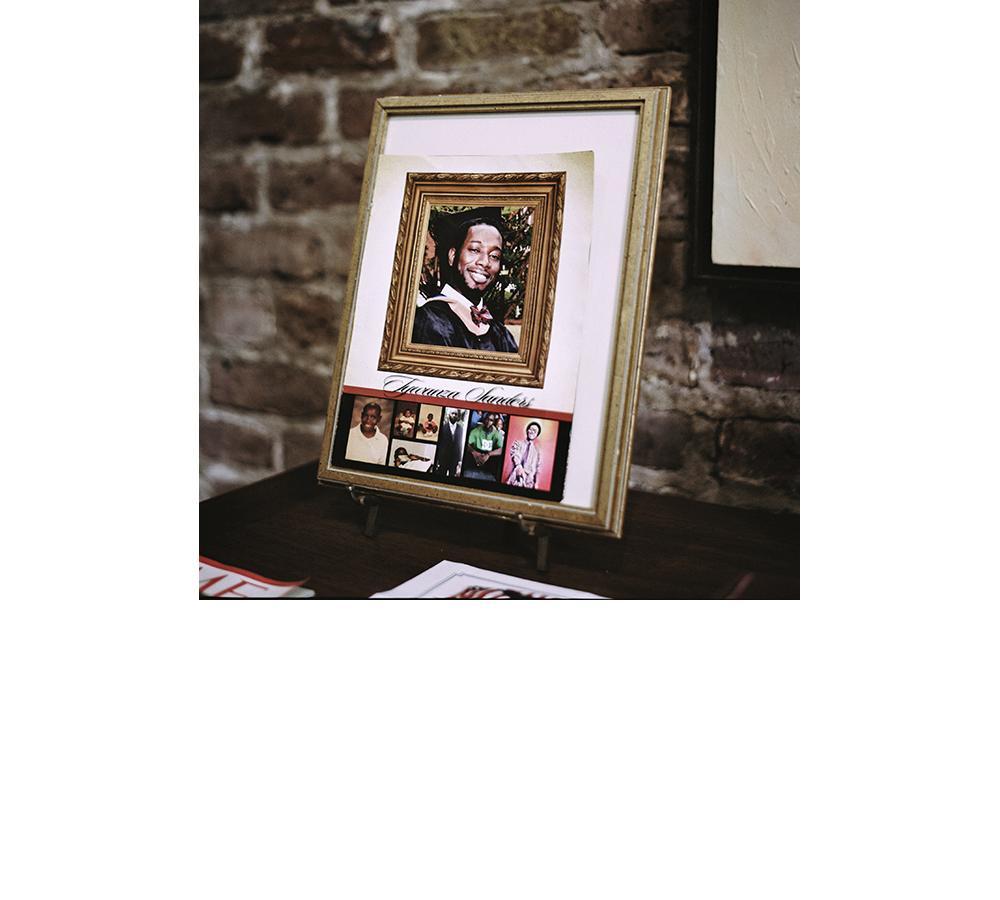

Pictured is a portrait of Tywanza. The image sits on the desk of the personal friend and lawyer representing the family. The overwhelming amount of media attention has been very hard on Felicia and has not allowed her to grieve, so now she goes through a spokesperson. “It’s one thing to deal with the death of a loved one—but given the circumstances under which he died—it’s thrust us into a whole new world. Dealing with media,” says Shirrene.

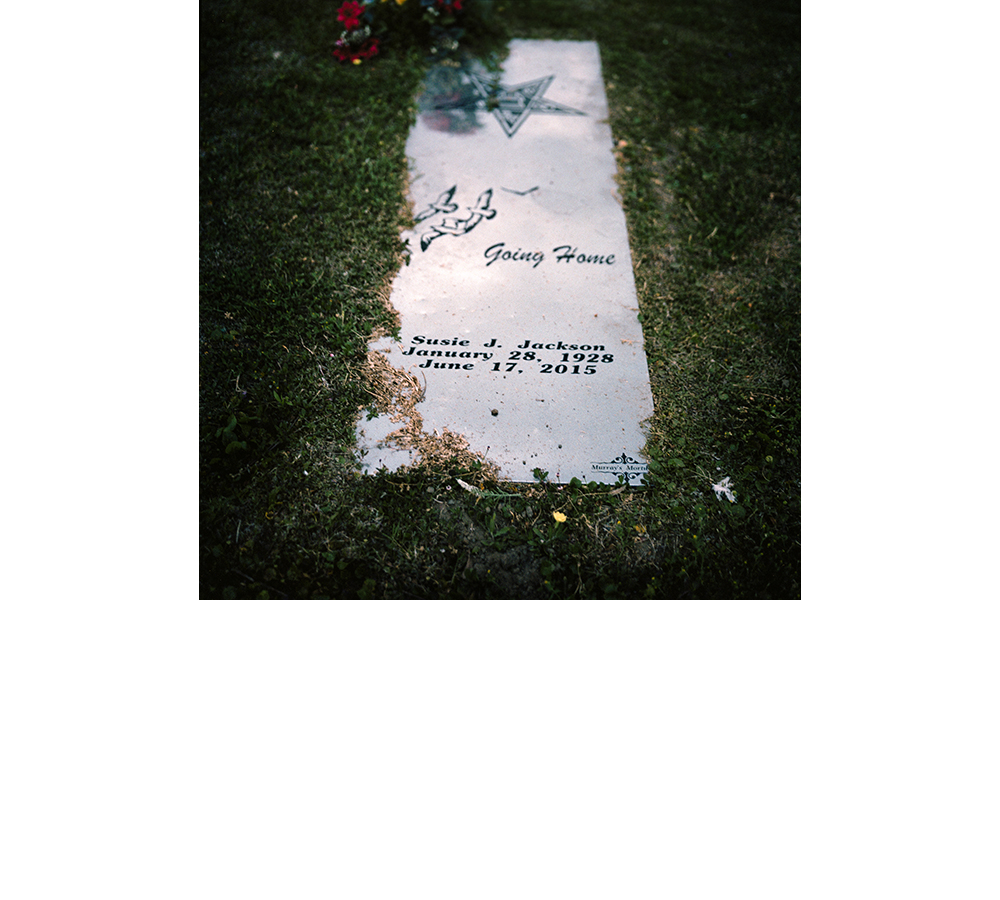

The grave of Susie Jackson, aunt to Shirrene Goss, is at the Mother Emanuel Church cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. Jackson was killed along with her nephew, Tywanza Sanders, at Mother Emanuel AME Church, on June 17, 2015. As Jackson lay dying, Tywanza, shot and bleeding, crawled over and tried to comfort her, according to his mother, Felecia Sanders, who was playing dead underneath a nearby table.

CHARLESTON: FRAGILE FORGIVENESS

PHOTOGRAPHY + TEXT BY JONATHAN HANSON

Recent Posts

Podcast Reviews

- Wonderful podcast

December 6, 2016 by JennieSewell from United States

December 6, 2016 by JennieSewell from United StatesI love story telling podcasts and this one is really wonderful. The tone is honest and has a great rhythm. When I hear someone's story I always want to know more about them, so the photographs are a beautiful addition.

- Creative!

September 4, 2016 by TrockfromGrock from United States

September 4, 2016 by TrockfromGrock from United StatesGreat Podcast! Very well done. Love the way the stories are told.

- Job well done by AFP

September 2, 2016 by RB406 from United States

September 2, 2016 by RB406 from United StatesA Face Project is great! These podcasts are well put together and fun to listen to. I really enjoy hearing the "everyday people's" stories, and listening to something positive and uplifting is a pleasant change from mainstream media. Keep up the good work!

- great sense of community

September 2, 2016 by Cally Jean from United States

September 2, 2016 by Cally Jean from United StatesAmazing series that exemplifies a sense of community and unity among us all.

- Great podcast!!

September 1, 2016 by nmgunn from United States

September 1, 2016 by nmgunn from United StatesBeautiful stories told in an elegant and fascinating way, a look at the world through someone else's perspective. 5 stars, a great podcast!

- Excellent

August 31, 2016 by BKLJ 123456 from United States

August 31, 2016 by BKLJ 123456 from United StatesEach story is thought provoking and insightful. We have so much to learn from each other, and A Face Project provides a comfortable and beautiful landscape for just that. Looking forward to hearing more!

- AFP

August 31, 2016 by Alleycat1989 from United States

August 31, 2016 by Alleycat1989 from United StatesI look forward to seeing more and more of this artists work! Love the unique and artistic way she presents the stories and photos. Excited to see what's next!!

- Inspiring Podcast

August 31, 2016 by ILoveTheSeahorses from United States

August 31, 2016 by ILoveTheSeahorses from United StatesLove the stories! Adding this to my regular listening list!

- Great podcast!

August 31, 2016 by Weathermanmd from United States

August 31, 2016 by Weathermanmd from United StatesLoved the podcast. Everyone does have a story!

- LOVE!!

August 31, 2016 by Schreibs47 from United States

August 31, 2016 by Schreibs47 from United StatesI love A Face Project podcasts. I find the stories to be touching, inspiring and heartwarming. I think this was such a great way to share stories from all over the world! I look forward to hear what the future podcasts bring ?

- A connection through voices

August 31, 2016 by MollyMJB from United States

August 31, 2016 by MollyMJB from United StatesI absolutely adore the connection I feel listening to these stories of real and raw experiences. They have quickly become my favorite commuting companions wandering through the city.

- Great Podcast

August 31, 2016 by JohnnyRad from United States

August 31, 2016 by JohnnyRad from United StatesThis is a great podcast full of interviews of everyday people who do great things. The stories are original and interesting. I love listening while working on my computer in the mornings. Highly recommended.

- Keep them coming!

August 31, 2016 by NaomMarie from United States

August 31, 2016 by NaomMarie from United StatesAFP is a great podcast to get lost in. The stories are eclectic, real life, and a treat to listen to. I can't wait for new episodes!

- Look forward to every episode!

August 31, 2016 by Lisa Quinlan from United States

August 31, 2016 by Lisa Quinlan from United StatesI love hearing all the stories about ordinary people and how they fit in to this world. Finally a podcast to listen to that's both uplifting and "feel-good"! Bonus content like the photos on the web make the people come to life.

- Amazing stories

March 24, 2016 by Ron Willson from United States

March 24, 2016 by Ron Willson from United StatesI listen to many podcasts and I love podcasts that tell a story. The wonderful thing about A Face Project is that it features inspiring stories from everyday people. This is now one of my favs. I look forward to more episodes.

- Creative first-person narration

March 24, 2016 by A Face Project from United States

March 24, 2016 by A Face Project from United StatesLove the first-person, non-intrusive interviewer format. Great stories!

- © A FACE PROJECT 2017

- CONTACT US

- SUBMISSIONS

- FAQ